| DRUG WARCan Santa Maria Kick It’s All American Habit?

[Editorial Introduction:

The term "War on Drugs" has been prevalent in our society in the last two decades. Yet, I would bet most people don't truly understand its meaning.

The overall feeling about this war is that it only rages in foreign drug producing countries, or on the streets of cities like New York or Los Angeles.

But it also rages here.

This week's cover story by John Dean brings the War on Drugs home. The story, packed with powerful numbers, shows how drugs take lives every year in Santa Maria, and ruin countless others. It also shows how drugs cause crime, and lower our overall quality of life. If you never thought the war on drugs affected you, this story may make you think otherwise.

Meet the hometown warriors [p 6] here in Santa Maria that are fighting to help those in the powerful hold of drugs, and improve the overall quality of life in Santa Maria. While the war they are fighting may nver be won, I think you’ll find the individual battles they are winning are making a difference.

Marla J. Pugh, Editor]

Santa Maria, the All America City, like other American cities, has become the front line in the war on drugs. Ours is a city known for its agriculture; its blue-collar, hardworking citizens; and, in some circles, its methamphetamines. With the methamphetamine has come crime and social problems.

According to Assistant Public Defender James K. Voysey, 75 to 80 percent of the felony cases in Santa Maria are drug related.

Those numbers have meant that Santa Maria police and other law enforcement agencies have placed the drug problem high on their priority list. Recent drug sweeps in both Santa Maria and Guadalupe have been aimed to reduce drug-related crime. In addition, two treatment programs available to those arrested are boasting high success rates.

Last year, the city’s Narcotics Unit arrested a total of 457 people on drug charges and the unit confiscated 9.5 pounds of methamphetamines. That compares to just 98.3 grams of heroin, and 702.6 grams of cocaine that was confiscated. Officials said that the drugs confiscated in Santa Maria alone last year were valued at more than $37,000.

“There used to be a fairly substantial cocaine problem,” said Voysey. “Now we don’t see nearly as much cocaine as we see meth. Cocaine is more expensive and harder to get. Methamphetamine is incredibly cheap and the high lasts a lot longer.”

It is common knowledge among those in the drug world that if you want heroin you go to Santa Barbara, but if you want methamphetamine you come here, officials said. Much of that is due to the social and economic factors that make up Santa Maria, officials say. The drug is relatively cheap and allows users to go without sleep for days at a time and work longer hours. Methamphetamine has been proven to be popular among blue collar workers and is even referred to as the “poor mans cocaine.”

The drug gives off an initial euphoric high. But when that ends, the user goes down to a state of dysphoria or depression, said Voysey.

“That’s why the drug is so dangerous. You go way high and then way down and it eats at your body,” said Voysey. “Hence when you get to that dysphoric state after a long period of use, you get real nasty and you don’t have much of a cushion, as far as your personality is concerned, for anything that goes wrong.”

That is exactly what happened about two years ago in Santa Maria when a 19-year-old man killed his mother and shot his stepfather numerous times. The man had no criminal history. According to Voysey, his actions were a direct result of the drug.

“People commit all kind of really heinous violent crimes because of that dysphoric or that depressed state of mind they get into,” said Voysey. “If they can’t get their drug and someone is in their face, there is a chip on their shoulder to begin with. A lot of them are armed to protect their dope, and then you have the paranoia, so they’re also armed to protect themselves. It’s a vicious circle.”

A circle that Voysey sees often.

“Santa Maria is typical of the meth problem that California is experiencing,” said Voysey. “It’s not more or any less here, but it is a constant ongoing problem that we deal with.”

Drug Sweeps

The Santa Maria Police Department Narcotics and Gang unit have been busy combating the drug problem in the city. About a year and a half ago, a large amount of resources were concentrated on drug abuse within Santa Maria and Guadalupe due, in part, to the high amount of residential burglaries. The burglaries were tied directly to drug users breaking into peoples’ residences and looking for money or valuables to finance their habit.

Officers made 174 arrests in drug sweeps throughout Santa Maria and Guadalupe last year and residential burglaries are now down 40 percent. This years’ sweeps have netted approximately 70 to 75 drug arrests in Santa Maria and Guadalupe.

Drug sweeps involve weeks of preliminary investigations after which the department goes out and makes numerous arrests in one day. This method protects informants from being identified. Most informants have been arrested for being under the influence, a misdemeanor, and then cut a deal with the police to go undercover and make buys from people they have purchased dope from before. In return for their help, the informant gets a lesser punishment.

The police corroborate the informant’s information by going undercover and trying to buy drugs themselves. If they are able to collect evidence, then a search warrant can be issued. But all tips have to be corroborated with evidence before a search warrant can be given.

Santa Maria officers are also currently training Guadalupe police officers in locating narcotics users. The city’s Narcotic Unit spend time in the classroom with Guadalupe officers teaching about the drug and the characteristics of the user. Those same officers are then partnered up with Narcotic Unit officers for field training.

The police use a seven-step process in identifying meth users, which includes identifying the telltale signs of meth abuse, along with other physiological changes to the body.

“Overall it’s a good thing,” said Guadalupe mayor Sam Arca. “As a society we need to function and feel relatively safe.”

Arca sees treatment as the long term answer to the problem.

“Intervention and prevention is the way to go,” said Arca. “Incarcerating them is not necessarily going to help them.”

Drug Court

Arca’s opinions on drug rehabilitation is shared by many. That is why, in 1996, the Substance Abuse Treatment Court, otherwise known as Drug Court, was created simultaneously in Santa Maria and Santa Barbara. It’s a minimum 18-month, five-phase outpatient program administered by Cottage Care. The program gives those arrested an opportunity to kick their habit and avoid jail time. If they don’t complete the program successfully, they are sent to jail to serve their time.

Graduates must also complete a GED program if they are not already high school graduates, and be gainfully employed upon completion. Social services such as job training and parenting classes are also accessible.

Even acupuncture, as a way to help relieve stress and calm withdrawal symptoms, is available for those who need it.

The treatment seems to be working. Drug Court has graduated a total of 120 people and has a success rate of 70 percent.

The program was patterned after the first drug court created by Janet Reno in Florida many years ago. Now there are almost 500 drug courts nationwide.

The fact that the program is working has not been lost on politicians. Recently, Gov. Gray Davis proposed a $10 million increase to the $8 million spent on drug court programs in the state. The funds will be used to add 15 new drug courts to the 65 that already exist in California. Included in that will be 15 drug courts specifically for juvenile offenders.

“The nice change is that there’s now accountability in treatment,” said Sue Green, Program Director. “Clients can’t hide in treatment to avoid legal action. This is a place where everybody puts it on the table and you have got to want to be here to succeed.”

Green has seen the success stories first hand.

“We have clients that are getting reunited with their children, getting custody back of their children. They’re reconnecting with their families,” said Green. “We have clients working everywhere in the community. It’s very difficult to go anywhere and not find some our clients working. That’s a nice feeling.”

One of the program’s best success stories is Mark Casto of Santa Maria, the first graduate of drug court. Casto says he is at a place five years ago he doubted he would ever get – he’s clean and sober. He looks back at his journey and is astounded that he has come so far.

“It’s just a miracle, said Casto. “It’s amazing.”

He began shooting up heroin at the age of 15 and admits to trying just about every drug possible, including methamphetamines. He made numerous attempts to get clean, even spending 13 years on a methadone maintenance program.

“I’ve tried every imaginable way to control my use of drugs and none of them worked,” said Casto.

At the age of 41, he moved here from southern California to kick his habit, but three or four days later he was back using again. Then his life took a turn for the better when he was arrested for being under the influence. Facing jail time, Casto adopted to go into the new program.

There were more than a few skeptics, and Casto was one of them. He didn’t put much faith in his own treatment because he had tried to stop so many times before and failed.

“No one thought that I was going to make it,” Casto said. “I was one of the harder cases. I was actually in there for like 20 months.”

He attributes the success of his recovery to the fact that drug court held him more accountable and educated him about his disease.

“I was basically monitored and educated,” said Casto. “A person can’t do better until they know better.”

Although his drug of choice was heroin, he sees little difference in the drug culture today and the one he came of age in. The drug has changed, but the problem remains the same, said Casto.

The only difference is in the education of police officers in fighting this problem. Specifically, he commends officers in Santa Maria and Santa Barbara County.

“I think the drug problem is the same everywhere, but the police here do a very thorough job,” said Casto. “The police are becoming very educated.”

Casto now works closely with the police and people in the justice system in improving treatment programs and educating the young. He sees educating children as young as 10-years-old as a preemptive attack against future drug abuse.

The recovering addict now has a new lease on life and admits that if it had not been for Drug Court, he would be in prison.

“I was 42 years old before I ever experienced total freedom,” said Casto, referring to the freedom he now has over his habit.

But Drug Court has strict guidelines. No violent offenders and no one who was arrested for selling drugs for profit are allowed in. That leaves a large element of people – and some may argue the worst element – still in the powerful grip of the drug.

Substance Treatment Program

For those offenders who have a history of violence, or who have sold drugs for profit, their last hope may be David Vartabedian.

Vartabedian runs the Substance Treatment Program (STP) in the Santa Barbara County Jail. The program offers counseling, education on addiction, and 12-step meetings for inmates.

The program began in 1996 with facilities for 21 inmates. That number has grown in four years to 83. Participants in the program are segregated from the general jail population. The treatment program has 53 beds for men and 30 for women. STP is perpetually full with an ongoing waiting list.

Before the program was created, jail officials noticed that 75 percent of those incarcerated had a problem with alcohol or drugs. From that percentage, 70 percent returned to jail after their release for charges that were somehow alcohol or drug related.

“The sheriff recognized that their was a problem that needed to be addressed,” said Vartabedian.

After a year and a half in operation, approximately 220 people completed the STP program and of that amount only 38 percent were re-arrested and returned to the county jail.

“That gave me a barometer that said this program is doing something,” said Vartabedian.

After completion of their jail time, about 60 percent of the graduates of STP enter into a transitional home for sober living, which helps to ease their transition back into society.

“The transition homes all say that the clients they get from the STP program have a good foundation toward recovery,” said Vartabedian. Because the first and foremost job of the jail is to protect the public, it is in the best interest of society to safely transition drug offenders back into our community, he said.

Vartabedian also points out that tax-payers do not pay for the inmates treatment. The program is funded from profits from the commissary and phone calls by inmates, as well as from a grant from the county.

The treatment program also differs from other programs because Vartabedian, three counselors, and an intern, are all Sheriff Department employees and their salaries are worked into the jails’ budget.

“So if funding runs out, we don’t go away,” said Vartabedian.

Vartebedian said the first thing the counselors do in the program is to get the participants to recognize there is a problem and to take responsibility for their actions. There are no victims in the program, he said.

“I think addiction has a lot to do with unachievable goals in society,” said Vartabedian. “We push that this is success and when you can’t achieve that you seek other outlets.”

Vartabedian also sees education and awareness as the key in fighting drug use.

“It [addiction] has been recognized as a disease by the American Medical Association for years, but as a society we’re still in the dark ages about addiction.”

He admits that sometimes the job can be tough. A jail drug counselor deals with travesties every day and are seeing people at the lowest point of their life.

“But going to the STP Alumni Association meetings and seeing the productive people they’ve become it’s a boost,” said Vartabedian. “They’re givers now instead of just takers.”

[Inset #1: Facts About Meth

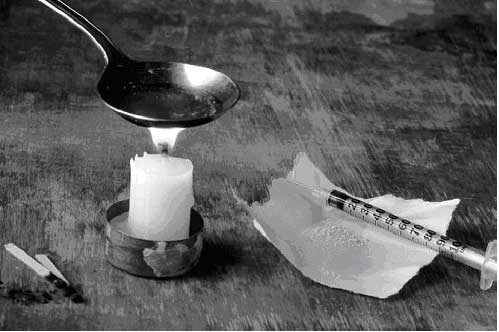

Methamphetamine can be smoked, snorted, swallowed or injected. The drug is very easily manufactured in home-made labs.

The precursor for meth is ephedrine, which often times comes in through Mexico or can be bought at some drug outlets or even over the Internet. The ephedrine is then "cooked" in a lab to create this drug.

Meth usually appears as a white powder or as whitish crystals in the case of "ice," a slang term for the smokable form.

Meth has been known to cause nausea, tremors, dizziness, hypothermia, heart failure and stroke.

Because the drug is produced in home-made labs, users take a chance that the substance is cooked incorrectly and that other chemicals or drugs are substituted.

The signs of meth use are very recognizable and include shrunken eyes, loss of weight and scabs on the skin. The drug causes paranoia and users think they have bugs underneath their skin, causing them to scratch and sometimes cause open sores.

Long term users mirror the symptoms of a paranoid schizophrenic. Users can experience severe paranoia, and audio and visual hallucinations. Although these symptons usually stop when the drug is cleared completely out of the body, they sometimes linger for weeks or even months. Scientists attribute this to damage of the neurotransmitters in the brain.]

[Inset #2: The Numbers

174 ... the number of arrests from drug sweeps throughout Santa Maria and Guadalupe last year.

70 - 75 ... drug arrests in Santa Maria and Guadalupe from sweeps so far this year.

40% ... the reduced amount of residential burglaries since police started doing drug sweeps in Santa Maria and Guadalupe.

75 - 80 ... the percentage of felony cases in Santa Maria that are drug related.

457 ... people arrested on drug charges in Santa Maria by the city Narcotics Unit last year.

9.5 lbs ... amount of methamphetamines confiscated by the city Narcotics Unit last year. That compares to just 98.3 grams of heroin and 702.6 grams of cocaine confiscated.

$37,000 ... the value of all drugs confiscated just in Santa Maria last year.

120 ... the number of people who have graduated from Santa Maria's Drug Court since it's creation in 1996.

70% ... the success rate of people staying clean after going through the Drug Court program.

220 ... the number of people who have completed the county jail's Substance Treatment Program in just it's first year and a half of operation.

38% ... the number - down from 70 percent - of people who were arrested again for drug-related offenses and returned to jail after going through the Substance Treatment Program.]

MAP posted-by: Jo-D |