Bangkok Post

From fighting the communist insurgency and drug smuggling, this one-time boy soldier is now branching out into a new line and new life

Published: 30/01/2011

Newspaper section: Spectrum

Heroin and coffee. These two words come to mind when Lao Ta Saenlee, 74, smiles, gestures and chats while sipping Chinese tea at his newly-opened coffee shop in his village, Ban Huay Sarn, in Chiang Mai’s Mae Ai district. While coffee is his new-found passion, Lao Ta has long been infamous and associated with drugs and heroin trafficking in the North. Although it’s been three years since he was released from jail, a renewed passion for life still bubbles from every word as he talks about plans of starting a franchise of “Lao Ta Coffee” shops across the North.

FROM JAIL TO JAVA: Left, Lao Ta Saenlee reflects on his life. Right, at the time of his arrest in 2003.

But he will never be able to dispel decades of accusations of drug trafficking _ an image attached to prominent former Kuomintang (KMT) fighters who fled southern China into Burma in 1949 before settling in the northern hills of Doi Mae Salong in Chiang Rai in the 1960s.

His name has been associated with the now deceased “Opium King” Chang Chi-fu, or Khun Sa, and the current drug baron, Wei Hsueh-kang of the United Wa State Army. He knew them both but vehemently denies drug links with them.

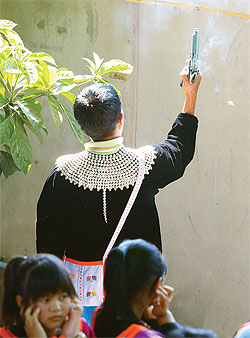

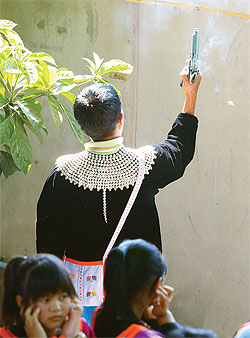

FIRED UP: New Year at Lao Ta Saenlee’s home.

Lao Ta’s story is one of a boy soldier and young fighter whose life was moulded and shaped through the barrel of the gun. It ensured his survival during times of political upheaval and in the dense jungle along the border between Burma and northern Thailand during the Cold War.

Like other prominent former KMT fighters, his leadership qualities gained him armed supporters, but invariably living in a foreign land meant agreeing to be a pawn in Thailand’s fight against the communist insurgency from 1961-1982. He fought the insurgents in exchange for a place to live, and as a result his stature and influence grew. But like so many others who often lived and trod on the shadier side of life with frequent encounters with the law, he fell from grace and was imprisoned.

Now he’s back _ but it wasn’t easy.

Lao Ta advises: Drug problem here to stay

During the height of the campaign against drugs by former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, police arrested and seized the property of thousands of suspects. About 2,500 were killed. In June, 2003, the authorities moved against Lao Ta.

”I remember that day well. It was 4 or 5am, and about 100 troops, cavalry and police surrounded my home and village. All entrances were blocked. They blocked the road leading to my home with a tank. They searched all the houses in the village. ”They searched for two days but they didn’t find any drugs. They arrested some addicts and they confiscated a lot of weapons. But it’s normal for hilltribesmen to have weapons. The villagers need the weapons to defend themselves. There was a large quantity of weapons and ammunition in my home,” he admits.

For the next four to five days, Lao Ta _ and two of his sons, Vijarn and Sukkasem, who were also arrested _ were flown to Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai for press conferences by authorities and then flown back home. ”They wanted to make a big story out of my arrest,” he recalled.

Lao Ta spent fours in jail (from 2003-2007) and faced four separate charges of illegal possession of 336g of heroin, trafficking in 400kg of heroin with intent to sell to Malaysia, hiring a gunman to murder a man in Chiang Mai’s Fang district and illegal possession of firearms and ammunition.

By 2007, the courts dismissed the drug trafficking and attempted murder charges because of insufficient evidence _ a result of conflicting testimony from prosecution witnesses. He was slapped with an 18-month jail term for illegal possession of firearms.

THE HILLS COME ALIVE: left to right, Lao Ta Saenlee enjoys New Year’s festivities at home.

Thaksin even suggested that Lao Ta’s defence capitalised on loopholes in the law and bribed his way out.

But while he was imprisoned, a sizeable chunk of Lao Ta’s cash _ ”I don’t have millions I have only 76 million” _ along with his properties, comprising a 300-rai lychee orchard, five houses in an up-market housing estate in Chiang Mai’s Muang district, and a supermarket in Ban Huay San, were seized by the government.

All that was left was his home, a petrol station and land that he acquired as payment for fighting the communists. The government could not seize the property because he and his family do not own it but have legally-issued documents allowing him and his to occupy and earn a living off the land.

”I had nothing left. My wife [he has three] had to sell 94 cows to live off while I was in jail. I could not even afford to buy pla too [mackerel] to eat,” he insists. At one point when he was feeling depressed, Lao Ta actually considered robbing a bank. ”I called up two of my most loyal supporters and suggested the idea. But they told me ‘Boss, we’re now 70 years old,”’ he said, smiling. He admitted thinking about selling methamphetamines but dismissed the thought quickly.

Fortunately, he got a call from ”a friend who used to traffic in drugs” who congratulated him on his release and asked how he was doing. Lao Ta told him that he needed money to get his life back on track. ”I told him I needed about six million baht. A few days later my friend put two million baht into my bank account. I tried to call and thank him but there was no answer and I have not heard from him since,” said Lao Ta.

GONE STRAIGHT: Lao Ta Saenlee, now hopes to own a chain of successful coffee-shops.

Financially replenished and feeling better, old habits die hard. Lao Ta held a party in the village to mark his freedom. ”We roasted pigs and had a grand party. I spent a lot.” But reality set in and he had to think long-term. Ironically, he thought about Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek. Both gave him the inspiration to move forward.

”In those days, both leaders headed countries that faced within insurmountable problems. They had nothing. But they both made something [their countries] out of nothing,” he said.

Lao Ta still had his home and the land. But he also had notoriety _ a name people dhremembered, at least in the North. And so the idea of Lao Ta Coffee was born.

Lao Ta’s resilience probably did not stem from his thoughts of Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek alone but because he’s had a life of struggle, depending on weapons to stay alive. Lao Ta says he ”dragged a gun” in Chiang Kai-shek’s army in southern China’s Yunnan province when he was just 13. In 1954, at 17, he joined remnants of the KMT’s 5th Regiment of the 93rd Division led by Gen Tuan Shi-wen into northern Burma. These forces fled Yunnan into Burma three years earlier and continued to fight against the forces of the new Chinese Communist regime.

In 1961, Lao Ta joined Gen Tuan and about 4,000 battle-weary KMT soldiers into Doi Mae Salong of Chiang Rai. In exchange for asylum in Thailand they fought Thai communist insurgents between 1961 to 1982. During this period they grew and sold opium to pay for their weapons. ”At one stage the Thai government asked us to choose between leaving for Taiwan or staying behind. Many decided to leave for Taiwan. I recall looking at a map of the world to find out where Taiwan was. We could see that we had to travel a great distance across the sea. I was scared of the sea and feared I could never return home [to China]. So I decided to stay in Thailand and Khun Sa did toowas the same like us,” Lao Ta recalled.

But his stay in Doi Mae Salong did not last long. He decided to move back into the Burmese jungles where he spent years trading in opium and building up his forces. ”We grew up with guns and weapons and over time we [including Khun Sa] started building up our forces.” Lao Ta said each individual leader built up their influence depending on the number of people loyal to them. He built up his followers from among the Muser, Lisu and Akha villagers.

”They spoke Chinese, so we could communicate with each other. You built up your position through your supporters and alliances with other groups. You needed this to survive. Opium was a commodity,” he said. ”I admit to having been a drug dealer,” he said in an interview in June, 2003, before his arrest. ”Back in the ’70s, in Doi Mae Salong, everyone did it. Opium was put in sacks and loaded onto helicopters. We didn’t have to take it to the market, buyers came to us.” He also admitted to having ”links” to Khun Sa after he took control of the Doi Lang area in the early ’80s. In those days Lao Ta himself controlled 700-800 armed men.

Lao Ta was not clear as to when he returned to Thailand. But when he did, he was invited to work for the Thai military. The deal was simple _ Lao Ta and his men could keep their weapons. They were paid half a million baht and given 500 sacks of rice. In exchange, they would fight the communist insurgents. Once their mission was completed, they were promised Thai citizenship and land. They would not own the land, but he and his men _ and their families and descendants _ would have the right to live off it.

”I helped the Third Army fight the communists for many years. I was involved in no fewer than 200 operations,” he said. Lao Ta and his men fought in Phayao, Nan and Phetchabun provinces and once were trucked to fight in the northeastern province of Loei. His military career ended in 1977, when aged 40, he was granted Thai citizenship and was allowed to live near Doi Mae Salong.

He settled in Tambon Ta Ton in Mae Ai district, and founded Ban Huay Sarn, the village where he lives now and which comprises 600 families and includes four smaller surrounding villages of 40-50 families each. He started growing cash crops and raised cattle obtained from Burma. But how does that explain the millions in cash and property he amassed in Chiang Mai by the time of his arrest in 2003?

Lao Ta admits that he knew Wei Hsueh-kang, the current drug baron, when Wei was based in Fang district of Chiang Mai before he joined Khun Sa at Ban Hin Taek in the Mae Chan district of Chiang Rai. When Khun Sa was forced out of Thailand, and as his influence waned, Lao Ta admits doing business with Wei when the United Wa State Army settled in Mong Yawn inside Burma near the San Ton Du checkpoint, which is close to his village. ”The Wa needed supplies, food … everything,” he said. Lao Ta adds however that he made ”a great deal of money” selling petrol to the Wa, especially when the Ban Ton Du checkpoint was closed. He paid bribes to get his 10,000 litre fuel trucks across into Burma. ”But I was never involved in drug trafficking,” he insists.

Over the years in Mae Ai district, Lao Ta’s influence grew, not only among villagers, but local government officials as well. He was involved in many community projects aimed at helping the villagers but he made sure he involved and worked closely with local officials and government agencies. He contributed openly and regularly to cash-strapped agencies. TVs, refrigerators and other office equipment at the local police station and district office bear the name of his other brother, Charan.

Although his relatives and close associates may have been arrested for drug trafficking, and Lao Ta had been involved in clashes with the law, before his arrest in 2003, Lao Ta was nominated twice as the best village headman in Mae Ai district. But ominous signs appeared on the horizon before his arrest _ the Chiang Mai governor dismissed him as village headman. Despite serving time, Lao Ta still enjoys widespread respect among the hilltribe villagers in the area who turned up in full force for their New Year celebrations at his home earlier this month.

The celebrations lasted three days and nights. There was singing and dancing. They lit firecrackers while village leaders fired their hand guns in the sky. ”It’s a chance to clean the barrels of their pistols,” quipped Lao Ta with a broad grin. Lao Ta provided the feast _ 30 pigs and 20 jars of home-made liquor.

The party was more joyful than it had been in previous years because Lao Ta was back to Ban Huay Sarn, the village he leads. And even though he’s now into coffee, his legacy continues _ his eldest son Vijarn, who served time with his father, is now the village headman.

http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/investigation/218928/heroin-and-coffee—the-saga-of-lao-ta-saenlee